A high school history teacher explains how he uses comics to engage students on challenging and vital topics.

By Tim Smyth

One of the more surprising bright spots of the pandemic for me was how much closer I became with students during remote learning. It’s much easier to unobtrusively pull a student into a one-on-one chat during a videoconferencing class than it is in a physical classroom. There are no other students listening in on a private one on one conversation. As an introvert myself, and with a son who can get lost in the shuffle in school, I know that many students will not ask for help, or even volunteer, in a public forum. These one on one virtual chats, during and after class, really helped the students and I to get to know one another as fellow human beings.

On the other hand, it was also more difficult to maintain appropriate boundaries between work and home. Particularly during the height of the protests against racism and profiling in Spring 2020, I had students emailing and messaging me at all hours of the night. I couldn’t stop checking my notifications because I knew these students were having a difficult time, and many of them had no one else to talk to.

Now that we’re back in the classroom, I want to remember the lessons learned during virtual learning and incorporate them with best practices for in-person learning. I know that students will again have a lot of challenging feelings to work through, especially as we are dealing with a global pandemic. I haven’t yet completely figured out how to recreate those improved personal connections, but I do know that comic books will be an essential tool in doing so, as they were during virtual and pre-pandemic learning.

Never Underestimate Curiosity

I have found a number of reasons why many students express themselves more freely through reading and discussing comic books than other mediums more commonly used in the classroom. Never underestimate curiosity in engaging students—many of my students have never even read a comic book when they come to my class—which is always exciting. Comics are less intimidating than the traditional textbook, which is dense with content vocabulary and shallow with exploration of topics. The format of comics allows for built-in scaffolding as images support text to help overcome language and reading barriers. They allow for the reader to sit at length to become emotionally involved in a deep dive into a topic. Comics help create analytical readers and writers on all levels as the students make meaning in a multi-modal manner. Images truly are representative of thousands of words and convey deep understanding.

As students create a comic, these skills and deep understanding are showcased in a powerful, engaging, and memorable way. Creating a comic is also a less intimidating way to assess the learning of students in comparison to traditional essays and research papers, although we certainly do those in class as well. Additionally, having students discuss their comics from their desk while it’s projected on the smartboard is not as scary as getting up in front of the class to give a presentation. Again, as a person who understands all too well the panic of anxiety, forcing formal presentations of memorized information is something I still struggle with as a middle-aged adult. Often, the creator only has to present a brief summary which then allows the other students to analyze and interpret it on their own. Another method is to have students leave their comics on their desks, or display a Padlet virtually, and then have students walk around the room in a gallery walk where they write down their reflection about each other’s comics. Here are a few specific comics projects that I use to connect with my students at the beginning of a new school year.

Building Community Through Personal Stories

This year in particular, we need to focus on building a community and welcoming students back, rather than just handing out textbooks, classroom expectations, and syllabi. There is already enough anxiety in the world right now, added to the usual anxiety of the first few weeks of school. I will have sophomores and juniors, coming into school after a year or more of virtual learning, some of whom have never been inside the high school building—all of our students have been through a lot in the last couple of years. My own children will be going through similar experiences as they return to school buildings that they have never seen, encountering fellow students whom they have never met.

I often like to start the year by surveying students about their interests, hopes, and fears. The most important question I ask is what they want me to know about them. I give these surveys throughout the year and they prove an invaluable resource to not only get to know my students in terms of academics, but also the music they listen to, what books they read, and what they want to learn. This year I’ll ask them to tell these stories with Pixton, a comic creation tool designed for the classroom. I often like to let students hand-draw their comics if they like, but for this assignment, I don’t want them worried about their artistic skills, plus Pixton is often faster and helps students get over the anxiety of a blank page. Pixton also gives students ready-made characters, backgrounds, and more that they can then manipulate and make their own.

I learned about the power of this lesson when I was blessed to be part of a wondrous global program through the US State Department. My colleagues and I worked with teachers and students from around the world, using original comics to help create empathy and to allow students to share their voice on vital topics. One student, from Southeast Asia, created an amazing, emotionally moving comic about her father dying right before Ramadan, which now makes it a more difficult time for her every year. My own father died from ALS the day before school began, and her comic allowed me to connect with her experience in a powerful and emotional manner. We sometimes forget that our students are all going through something, just like we are as adults. This student was able to create a “simple” comic to be shared that transcended language and place.

This year, I’ll share my own story and this girl’s comic, and then I’ll ask my students to tell me a story about something that defines them, or about what the last year was like, or what they are looking forward to or worried about in the coming year—anything they think is important about them, really. You can see many of the comics our global educators and students created at americanenglish.state.gov. I would also highly suggest following my inspiring colleagues in this program, Jacquie Gardy (@jacquiegardy), Jennifer Williams (@JenWilliamsEdu), and Dan Ryder (@WickedDecent).

Developing Empathy Through Comics without Borders

Another comics project I assign at the beginning of the year relates to the civil rights movement. Each year, my students read the March graphic novel trilogy co-written by Congressman John Lewis and Andrew Aydin and powerfully illustrated by Nate Powell. We do a lot of research, discussion, and soul searching through this powerful graphic memoir series. We understand that civil rights was not just an issue in the sixties and not just a Black and white issue. Instead, students can make many connections to events today and to issues around the world.

I know that educators in other countries also read the March trilogy for the same reasons and I love to connect with them through social media. (I am @historycomics and you are welcome to join the conversation on our collaborative Facebook pages as well - “Teaching With Comics” and “Comic Book Teachers”). Comics are truly universal and students around the world love them.

As my students create comics and discuss pop culture, we also have powerful exchanges with students in many other countries. A great way to use a resource like Pixton is by having students work on comics in a team-based, collaborative way on their computers—no matter how far apart they are physically. In an ever-changing educational setting between schools going all virtual, having some students in person and others virtual, and many absences, this ability is indispensable. In the past, we have been able to have students in other countries create these comics with my own students, so certainly students can do this should they find themselves virtual again.

That overseas experience led to powerful conversations about civil rights as my students often think that this is only an issue in the United States. But of course there are LGBTQ issues, issues related to immigrants, disability issues, and on and on. One way we explore the different kinds of civil rights struggles around the globe is by having students choose a modern civil rights issue to research and then use Pixton to create a research-based comic. Students from both countries are set up in small groups to research and create in a way they see best fitting to their strengths. Some choose to have students in one country create the first half and the students in the other country finish it. Some work together on each panel throughout the entire process. Some split up into roles—a researcher, an illustrator (often hand-drawn and combined with Pixton), a storyboarder, and others. This format allowed for an easy, yet deeply analytical experience, allowing students in both countries the chance to broaden their perspective about another culture.

Exploring Representation

Another comics activity that we’ll do early this fall is to create an avatar in Pixton and make a class photo with them. This was something I noticed a lot of teachers doing during remote learning because it’s a fun and easy way to create a little sense of community. Maybe we can’t actually be together in a room, but at least we can have a class “photo.” My own daughter’s teacher did this with her virtual classroom and each student was able to be represented in a fun class photo. The creation of an avatar is not just a simple activity, but one that forces students to really think about what makes them unique. How do they want themselves to be visually represented? What makes them special?

It can also be an opportunity to start a conversation about identity in a low-conflict way. When I first did this activity a couple of years ago, I noticed that some of my white students were having fun with hairstyles, clothing, and accessories that are associated with other ethnicities. So I talked to the class about cultural appropriation and why this can be offensive and harmful. I was sure to keep it general and not to call any particular students out, but when I was looking through their work that evening, they had of course changed their avatars to better reflect their own true identities. This was a great way to introduce the tone of the course—that we respect each other and honor our differences.

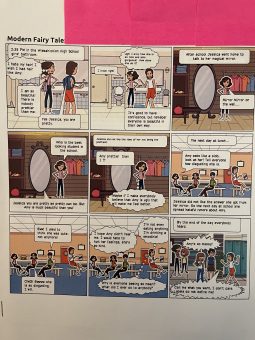

Finding Solace in Fairy Tales

I want my students to understand that stories reveal a lot about the people and cultures who create them, which is an important concept when I ask them to research fairy tales from around the world. After discussions about the original text, I ask them to put a modern twist on an existing fairytale and put it into comic form. The sense of freedom students get from retelling ancient stories in comic form sometimes leads them to open up in extraordinarily personal ways.

Last year, a student chose to reimagine Cinderella as a story about his own transition. He was having a really tough time because his father was still calling him by his deadname and using female pronouns when talking to or about him. Instead of an awkward conversation with the class, or perhaps even worse, many awkward conversations with different classmates, he was able to share it through a comic in a simple and compelling form. Maybe we can chalk it up to this student’s significant artistic talent, but he was perfectly comfortable sharing in that way and it allowed him to share his experience with his peers.

In the end, we all have different strengths and weaknesses, and we all have different ways we feel comfortable sharing our ideas and feelings with other people. In my classroom, comics have provided a powerful way for students to connect personally and to build that sense of community that we all need—especially in these traumatic times.

Tim Smyth teaches social studies at Wissahickon High School. He has written teacher guides and curriculum for using comics in the classroom, is an author at PBS writing about teaching with comics, and has a book forthcoming summer on the subject. He can be reached at [email protected] . You can also find many educational resources on his website, TeachingWithComics.com.

Tim Smyth teaches social studies at Wissahickon High School. He has written teacher guides and curriculum for using comics in the classroom, is an author at PBS writing about teaching with comics, and has a book forthcoming summer on the subject. He can be reached at [email protected] . You can also find many educational resources on his website, TeachingWithComics.com.